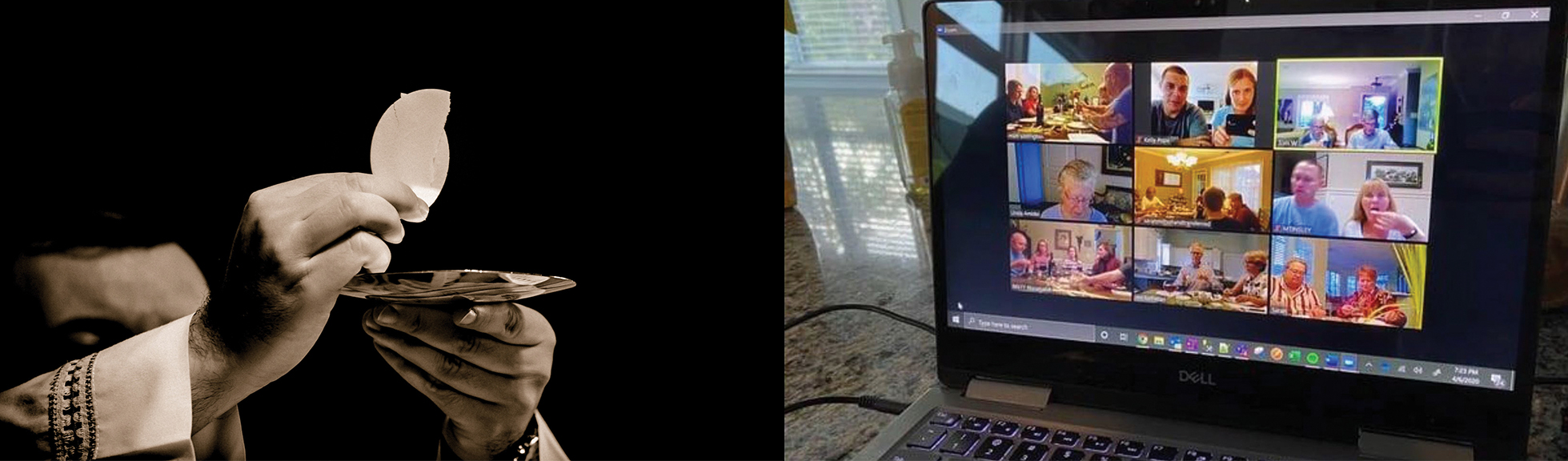

The people of St. Mark’s, Huntersville, gather online for a Seder meal. Photo by Kelly Pope

One of the “side effects” of the coronavirus pandemic has been the discovery—or expansion—of our use of video conferencing as part of the new normal. Much ink already has been spilt about the pros and the cons of this new modality. As we look ahead to a time when we can begin to move about more freely and gather for worship and other opportunities for in-person fellowship and contact, I wonder what we are learning about this way of communicating that may come in handy even after we are able to meet again in person, and about how and when to continue using this tool.

EMBRACING THE DUAL MODALITY

I think we are all clear that going forward, our worship will embrace the dual modality of in-person and online gatherings to some degree. The hybrid approach, as we have come to call it, makes sense from a variety of perspectives. It can reach those who are not geographically proximate. It can connect us with those who are not able to leave their homes, for whatever reason. It can serve as a wider witness to the activity and life of our congregations and the communities we serve.

Zoom, of course, is a brand name. But if name recognition is any indicator of brand success, Zoom takes the prize, as its name has become synonymous with the activity of video conferencing no matter what brand you are using, much the way Band-Aids became identified with plastic bandages, Xerox with photocopying and Kleenex with tissues in an earlier generation. The brand itself has even been “verbed,” as Calvin and Hobbes might have put it. The word “Zoom” has become shorthand for the activity itself, of connecting a group of two or more people on a video conference. “How many times have you Zoomed today?”

It may come as a surprise, but some of our churches have actually chosen this mode of communication over or in conjunction with Facebook, YouTube and other streaming channels because of its interactive dimension. And some of those congregations have actually grown during the pandemic. One of the big questions has been, how will that growth translate when we are no longer limited to remote contact?

And, of course, our use—or overuse—of this method of communicating has given rise to such terms as “Zoom-fatigue” and “Zoomed out,” or my personal favorite, “Zoombutt,” which is what happens when you have been sitting for too long in the same position, staring at the screen full of people in little boxes.

There are advantages, too. The cost savings in both gas and time by doing our business this way has been significant. The opportunities it creates for people to work remotely and/or from home create flexibility and savings in other ways. But how will it work for worship, or vestry meetings, or confirmation classes, or planning for the annual Christmas Fair?

These are the challenges that await us and are even now on the horizon. What will it look like to have people at church and people on Zoom as part of our Sunday morning liturgy?

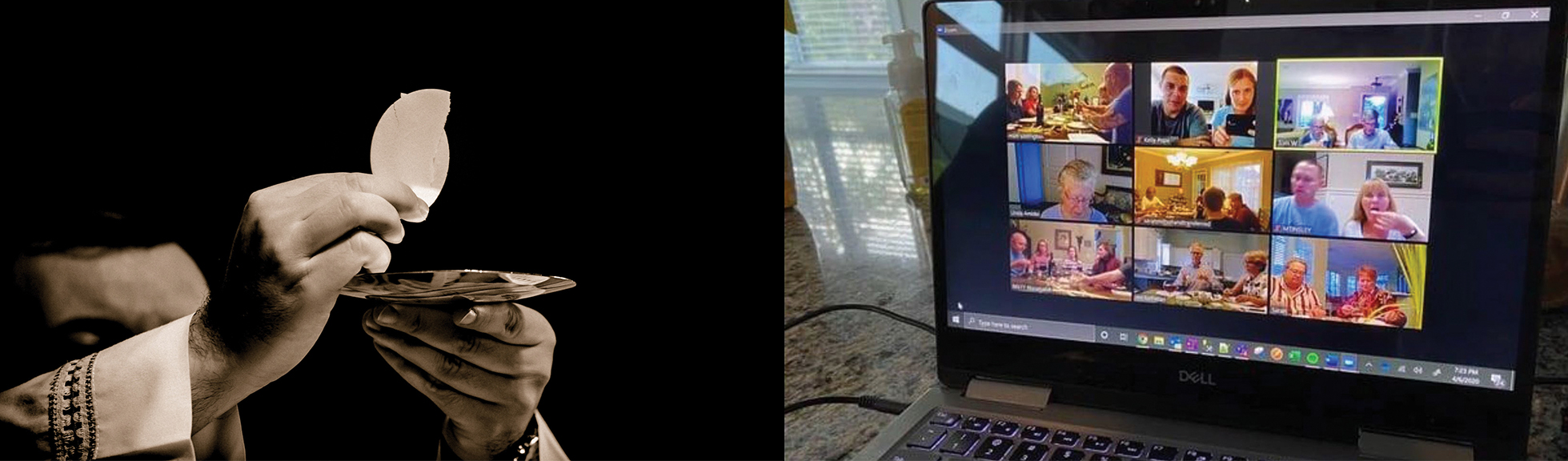

AN INCARNATIONAL CONNECTION

The image that comes to mind when I ask this question is of sporting events where large screens have been set up and athletes approach the screen to celebrate after scoring a goal or a touchdown. Or shows where singers or dancers perform live and those at home are able to join in real time by watching and affecting the outcome through voting and participating via social media. It is a way of bridging the gap when people are not attending the games or performances in person. But going forward, when we do have people worshiping together in our sac- red spaces again, the challenge is a more significant one.

How do we connect the Body of Christ gathered in our sanctuary with the members of the Body dispersed throughout the wider community and joining us electronically?

Oddly enough, there are a couple of biblical precedents for this challenge. When the Jewish people were permitted, after decades in exile in Babylon, to return to their homeland of Israel, not everyone chose to return. One of the challenges for those who did return was to find a way to be connected to those who stayed, who later became known as the diaspora: faithful Jews living outside of Israel. It was the traditions and liturgies of their faith life that provided the connection.

Much later, in the early days of the Jesus movement, as Paul moved beyond Israel and began to share the Good News of the Gospel in Asia Minor and other parts of the Mediterranean, a similar challenge arose. What was the relationship between the Church centered in Jerusalem and the churches that had sprung up as a result of St. Paul’s missionary journeys? This challenge was further complicated by the reality that many of the new converts were of gentile, not Jewish, descent.

Here again, the practice of worship played a vital and key role. Much of Paul’s epistles, as well as the accounts in the Book of Acts, document these early Church challenges and struggles. Here again, the case can be made that ritual practice and customs of worship played a major role in forging the connection.

This history suggests that, as Anglicans, we may have something particular to offer to the Church at this time as we seek ways to embody an incarnational connection between what happens in church and what is happening in our homes. In fact, it may be this connection between worship in church and worship at home is an unexpected and yet redemptive dimension of our response to the pandemic.

In the weeks and months ahead, I want to invite us, together, into this conversation. I am hopeful conversation will lead to experimentation, experimentation will lead to new models, and new models may lead us, as a Church, to create and embrace new ways of honoring the sacrament and promise of communion even as it extends to people who are not physically present in our sanctuaries.

There is a well-known hymn, the title of which is antiquated and uses language that we would not use today: “Once to Every Man and Nation.” But it contains the line “[n]ew occasions teach new duties.” This is such an occasion. The time is right to open up the conversation, to open our hearts to the movement of the Holy Spirit, and to reconsider the limits of our sacramental understanding in light of the limitlessness of God’s grace. The time has come, the moment is now, to open up the Church to such possibilities and to consider the full potential of the gift we have been given that is at the heart of our identity as a sacramental and incarnational Church.

The Rt. Rev. Sam Rodman is the XII Bishop of the Diocese of North Carolina.