Disciple: The Truth of It All

The continuing significance of our racial history

By The Rev. Dr. Brooks Graebner

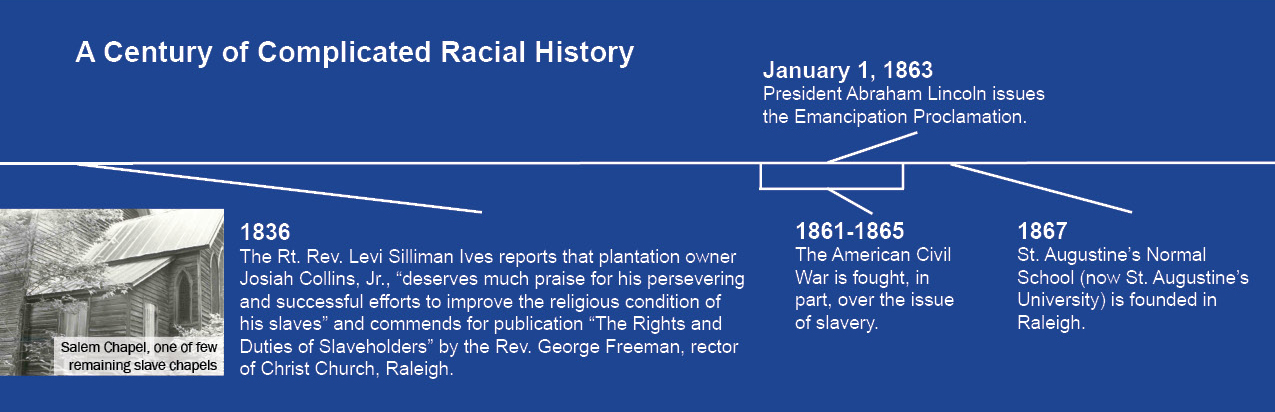

Timing can be a blessing. In mapping the path leading to the 2017 bicentennial celebration of the Episcopal Diocese of North Carolina, it’s long been planned that History Day 2015 would examine the history of race relations in our church and diocese. Never did we imagine that current events would so directly demand an honest examination of the subject and bring to light the need for ongoing conversation. It is for this reason the timing is a blessing, for only by acknowledging and refusing to hide from our past can we be more honest in the present and in our efforts to find a way forward.

THE PROFITS, PATERNALISM AND PROPHETS

The racial history of The Episcopal Church in North Carolina is bound up with the larger story of slavery, segregation and the struggle for equality in our state and nation. To tell this story truthfully requires us to confront the inherent brutality and enormity of slavery in America.

As we now know, the slave system was highly profitable, and many Northerners as well as Southerners were complicit in its perpetuation. To justify the ongoing enslavement of Americans of African descent, noxious and untrue racial theories were put forth.

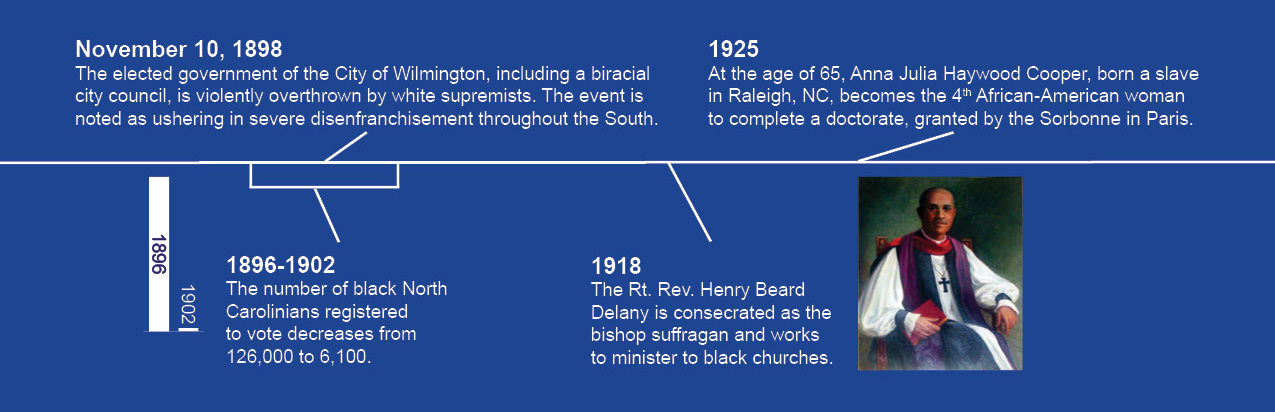

Sadly, these racial attitudes were not significantly revised after emancipation, and within 30 years of the Civil War, African Americans once more suffered the wholesale stripping away of their civil rights and economic opportunities. In North Carolina, this was accomplished in part by a violent coup that saw the duly elected government of the city of Wilmington forcibly removed from office in 1898. Tellingly, in 1896 there were 126,000 black North Carolinians registered to vote; by 1902, that number had shrunk to 6,100.

It would be comforting to be able to say Episcopalians had nothing to do with these sordid deeds, but the record proves otherwise. Episcopalians were among the largest and wealthiest slaveholders in the state and among the jurists and politicians who countenanced the worst features of slavery and legal segregation.

But there is more to our story than that. The Church could not completely forego its sense of moral and spiritual obligation to African Americans; consequently, considerable efforts were made to evangelize slaves. All the antebellum bishops of North Carolina encouraged slave evangelization and applauded those who built slave galleries and plantation chapels or who saw to the catechetical instruction of the enslaved members of their households and communities.

From our vantage point, we can see how flawed these efforts at slave evangelization were. Because the teaching often emphasized the moral obligation of slaves to be obedient to their masters, these efforts are often regarded by scholars as little more than veiled efforts at social control. But for all its defects, the witness of the Church to the reality of blacks and whites as co-religionists and children of the same God helped to form a cadre of devout and loyal Episcopalians within the African-American community. Pauli Murray’s grandmother, Cornelia Fitzgerald, is an example of someone who remained fiercely loyal to the Episcopal Church even though she was brought to it by her mistress, Mary Ruffin Smith, while Fitzgerald herself was still enslaved.

A NEW CHAPTER

Emancipation marked a new chapter in the history of our church’s relationship with African Americans. For the first time, blacks in the South were free to form their own churches and schools, and many availed themselves of these new opportunities. Our own bishop, the Rt. Rev. Thomas Atkinson, was in the forefront of those who wished to see the Episcopal Church embrace the moment. He urged the diocese to support educational efforts for the newly emancipated black population and to establish black congregations under black leadership. He also encouraged the Freedman’s Commission of the Episcopal Church to come to North Carolina to establish schools, which they did in New Bern, Wilmington and Fayetteville. The crowning achievement of these efforts was the establishment of St. Augustine’s Normal School in Raleigh, which remains to this day the flagship African-American institution of the Episcopal Church.

As a result of these early efforts to provide educational and religious opportunities for African Americans, the Episcopal Church in North Carolina became home to a number of remarkable black leaders. Henry Beard Delany first went to St. Augustine’s as a student. He remained there as a priest and professor, later becoming a bishop with oversight of black congregations in seven dioceses. Anna Julia Haywood Cooper grew up in Raleigh, attended St. Augustine’s, married a member of the faculty, became a prominent writer and educator and the fourth African-American woman to earn a doctorate. Pauline Fitzgerald Dame, aunt and namesake of Pauli Murray, went to St. Augustine’s as a 10-year-old, earned her public school teaching certificate at the age of 14 and embarked on a teaching career in the Durham schools that lasted more than 50 years.

Remembering the stories of great African-American figures like Bishop Delany, Anna Julia Haywood Cooper, Pauline Fitzgerald Dame and Pauli Murray serves to remind us that the Church in North Carolina has a racial legacy that weaves together more than one strand. The horrors and injustices of slavery and segregation, and the Church’s complicity in them, should not be minimized. But neither should the Church’s efforts to evangelize slaves and minister to African Americans be brushed aside. However flawed, the antebellum Church did make an effort to incorporate blacks and create a biracial worshiping community. These efforts gave impetus following the Civil War to more robust efforts to afford the newly emancipated with educational and religious opportunities, leading to the creation of significant black congregations and black institutions.

The results were not all that we could have desired. The Freedman’s Commission of the Episcopal Church, like other Reconstruction-era programs, was not sustained at a level commensurate with the need. The deeply entrenched racism in both church and society made it difficult to sustain even the modest gains toward racial equality of the 1860s and 70s. But the fact that such efforts were made, and the fact that a remarkable cadre of black leaders emerged from the 19th-century Episcopal Church in North Carolina, are surely worthy of our grateful, if belated, recognition.

The Rev. Dr. Brooks Graebner is the rector of St. Matthew’s, Hillsborough, and historiographer of the Diocese of North Carolina. Contact him.