Disciple: Holy Disruption: Worship, Liturgy and Race

By the Rev. Jemonde Taylor

Though many would like to think otherwise, sometimes Christian practices can do more to reinscribe racism than disrupt racism. The images in the stained-glass windows and Sunday school lessons, the hymns sung and types of music played, the sermons preached and scripture read, and other liturgical practices can all be, and have been, vehicles advancing a theology of white supremacy, the belief that one race is superior to another. Theologian Dr. Jay Kameron Carter believes Western Christianity is the suturing of white supremacy and Christianity. Saint Ambrose, Raleigh, a historically black Episcopal congregation, is committed to the “un-suturing” of white supremacy from Christianity through worship and educational practices.

[The Most Rev. Michael Curry blessed the icons of three African American Episcopal saints, including Blessed Pauli Murray, at the church’s sesquicentennial celebration in December 2018.]

The hope is to ensure all see themselves as beloved children of God. Worship spaces should be uplifting and community-centered, where one feels connected to the divine. The truth is many beloved Christian traditions do not grant that to people of color. In examining the traditions of Christian practice from the point of view of those who have rarely seen themselves reflected in imagery, vocabulary or music, the goal is not to choose one over the other—or to condemn the practices themselves—but rather to show how powerful it can be, and how much deeper the meaning of those traditions go, when what surrounds Christian practices opens to embrace and reflect every child of God.

ICONIC IMAGES

Jesus is the icon of the invisible God. - Colossians 1:15

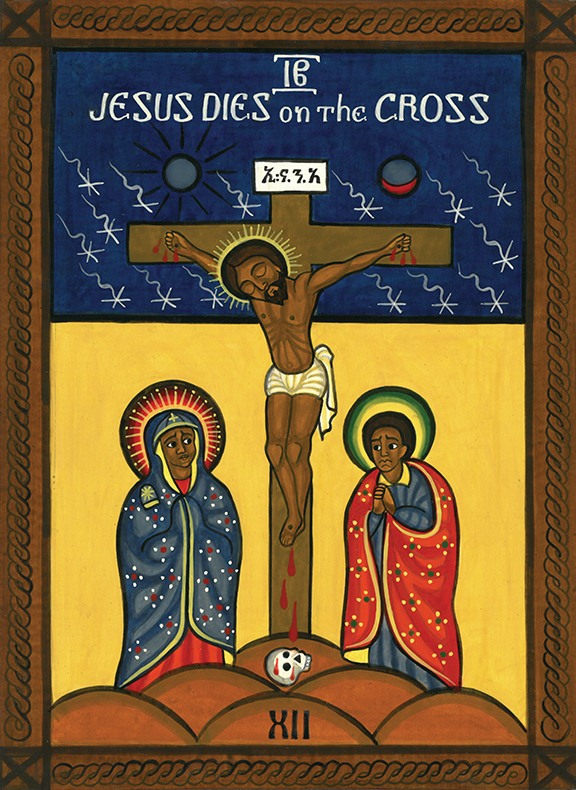

The passing of the peace at Saint Ambrose is an extrasensory experience of smiles, laughter, hugs and handshakes. One Sunday, I observed an eight-year-old member taking the hand of another eight-year-old boy visiting Saint Ambrose, leading him to the newly installed XII Station of the Cross written in the Ethiopian iconographic tradition depicting all characters as Africans. Pointing to the icon, the young church member said, “See? Jesus looks just like you!” Both boys were African Americans. The eight-year-old made a profound theological statement. He did not say, “You look like Jesus,” meaning the human looked like the divine. He said, “Jesus looks just like you,” meaning the divine imprint was on this young African boy.

That XII Station of the Cross in the Ethiopian Orthodox Christian tradition hung as the only station in that tradition at that time. The other 13 stations were 30 years old and lithographs of stations originally painted by the Italian artist Giuseppe Vicentini, born in 1895. Jesus, in those Italian paintings, had pale skin and blond hair. That Sunday, both eight-year-olds passed four other Italian Stations of the Cross to get to the one Ethiopian Station. It was in that Station both boys saw the divine in themselves, not Jesus in the Vicentini paintings.

The journey to the Ethiopian Stations of the Cross took nearly three years. After one year of searching unsuccessfully online and in stores for ethnically diverse stations, I commissioned D.C. Christopher Gosey, an African-American icon writer, to write the stations in the Ethiopian tradition. They took two years to complete, and according to Gosey, Saint Ambrose may be the only church in the world with Stations of the Cross in the Ethiopian iconographic tradition since stations are not a part of Ethiopian spirituality. Ethiopia is an example of what I term Indigenous African Christianity, which is Christianity in Africa before European colonialists and slave traders. The goal is to infuse this into the religious experience of Christians of African ancestry in the diaspora.

In addition to the Ethiopian Stations, Saint Ambrose received the gift from the Rev. Canon David W. Holland, TSSF, of three icons of three African American Episcopal saints with connections to Saint Ambrose: Blessed Anna Julia Cooper, Blessed Henry Beard Delany and Blessed Pauli Murray. Saint Ambrose celebrates two of the feast days by processing the icons to the burial sites of Blessed Cooper and Blessed Delany to offer prayers. Along with the icons, the Saint Ambrose needlepoint ministry, sponsored by the Episcopal Church Women, is making kneelers and pillows highlighting black saints such as Saint Augustine of Hippo; his mother, Saint Monnica; Blessed Henry Delany; Blessed Anna Julia Cooper and Blessed Pauli Murray. Last but not least, Christian formation examined the Sunday school materials used to educate Saint Ambrose youth, opting to abandon a long-held curriculum in order to embrace one with more diverse images.

THE BREAKING OF BREAD

We who are many are one body, for we all partake of the one bread. - I Corinthians 10:17

My friend is a professor at an Episcopal seminary. She once told a group, “One day in the chapel, the celebrant used baked Communion bread, having many shades of brown and black. I realized it was the first time I saw myself in the breaking of the bread.” Her comment made a profound impact on me. In 2017, I spoke with our altar guild about using whole wheat Communion bread instead of bleached white hosts. I felt disconnected placing bleached white bread into black hands.

THE POWER OF WORDS

The word is very near you. - Deuteronomy 30:14

Words are extremely important for what they communicate explicitly and implicitly. A scene from Spike Lee’s 1992 movie Malcolm X powerfully illustrates this. Brother Baines takes Malcolm to the library to look at compound words using black and white. All of the words containing black are negative: black sheep, blackmail, blackball and blackguard. The words associated with white are positive: whitewash, white magic, white knight and white lie.

Biblical dualistic language of light and dark was a convenient vehicle for mapping race. Light is white is European is good. Dark is black is African is bad. Even though there are positive images of darkness in scripture, rarely do parishioners hear them. The Ten Commandments found in Exodus 20 are read twice in the three-year lectionary cycle. Though nearly every other verse is read, both readings exclude Exodus 20:21: “Then the people stood at a distance, while Moses drew near to the thick darkness where God was.” Someone who faithfully attends worship will never hear that scripture giving a positive image of darkness, so I preach sermons using positive images of darkness found in the prayer book, such as the Collect for Christmas Day, and writings by Eastern Orthodox theologians that have positive images of God and darkness.

LIFT EVERY VOICE AND SING

Sing to the Lord a new song. - Psalm 96:1

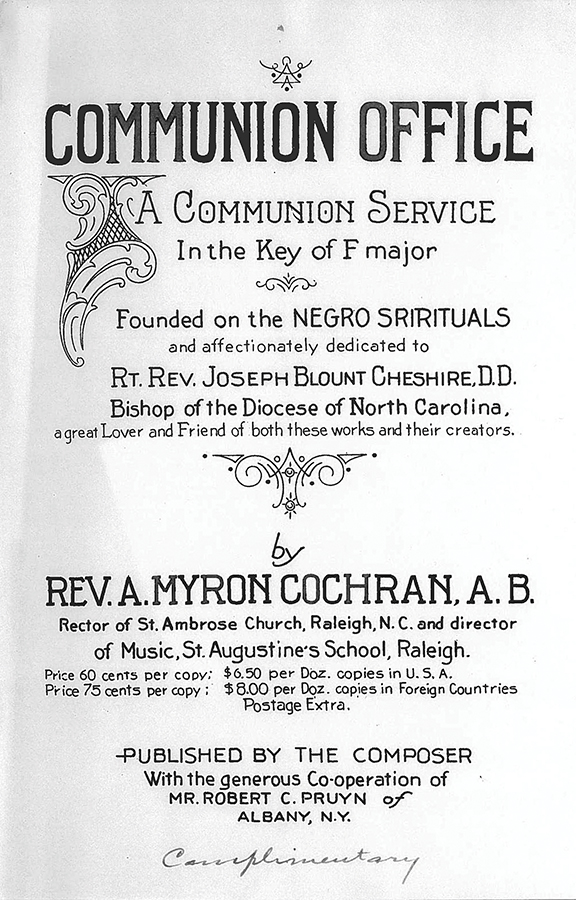

The Rev. Arthur Myron Cochran was both rector at Saint Ambrose and director of music at Saint Augustine’s University from 1919-1928. I call him the “Quincy Jones of the early 1900s.” In 1925, he composed an Episcopal service music setting based on Negro Spirituals titled, “A Communion Service in the Key of F.” Music historians credit him with helping revitalize the worship experience for African Americans. In 2018, Saint Ambrose commissioned the Rev. William Bradley Roberts, music professor at Virginia Theological Seminary, to update the text to language consistent with the 1979 Prayer Book while maintaining the spirit of the music. Saint Ambrose uses this as the principal service music setting. In addition to the Cochran Mass, Saint Ambrose historically has the Jazz Mass, a service infusing jazz with hymns and songs in the worship context.

Saint Ambrose also critically examines hymns, and the congregation has a banned hymn list. First on that list is a hymn beloved in Episcopal congregations, “I Want to Walk as a Child of the Light,” #490 in the Hymnal 1982, with the refrain, “In him there is no darkness at all.” The refrain comes directly from I John 1:5. However, the unintended consequence is the refrain plays into the language of biblical imagery of light and dark mapping to white and black for race. It is not possible to square that hymn with Exodus 20:21 describing God dwelling in darkness. Another song on the list is popular in African American churches, “What Can Wash Away My Sin?” The refrain has the line, “O precious is that flow, that makes me white as snow.” Imagine what is it like for a church of worshiping black people to sing about being made “white as snow.” Instead of the aforementioned hymn, Saint Ambrose explores singing hymns that affirm darkness, such as #702 in the Hymnal 1982 based on Psalm 139. Another affirming hymn is by Brian Wren, “Joyful is the Dark.”

BAPTISM

Marked as Christ’s own for ever. Amen. - Baptism Service from Prayer Book, 308

I baptized my first black person after arriving at Saint Ambrose, three years into my ordained ministry. I remember baptizing him on All Saints’ Sunday in 2012. I held this dark brown infant in my arms, wearing the baptism gown his great grandmother made. After pouring water three times over him, I placed my thumb on his forehead with chrismation oil, saying, “You are sealed by the Holy Spirit in Baptism, and marked as Christ’s own forever. Amen.”

The word “marked” carries heavy baggage for persons of African ancestry in the Western Hemisphere. During slavery, slave owners marked or branded enslaved Africans, showing ownership. Some American religious leaders in the 19th century, including Episcopal bishops, pointed that Africans bore the “Curse or Mark of Ham.” This mark was the “dark skin and wide nose.” Those espousing that doctrine used Genesis 9 as the basis for their belief, and others as the justification of racism and the enslavement of Africans. Even today, black people in the American context are marked subjects, victims of racial profiling and gun violence. In the black person’s psyche, marked is a loaded term.

Yet in the context of baptism and chrismation, death and destruction are brought into new life. The word “marked,” which in prior and current times meant slavery, cursed, without soul and death, in the context of baptism becomes the promise that God marks us as God’s own.

In order to punctuate signs of God’s abundant grace and love, the clergy baptize babies naked, submerging them in a 22-gallon baptismal font. For christmation, the clergy anoints the infant with at least four cups of holy oil. The parents rub the oil over the infant’s entire body for all to see holy oil on black bodies. The aroma of the oil fills the worship space.

WORSHIP

Worship the LORD in the beauty of holiness. - Psalm 96:6

Worship is central to the Christian’s life, and liturgical practices can be disrupters to the legacy of white supremacy, instead reaffirming our connection to the divine. Sunday of the Passion: Palm Sunday launches Holy Week at Saint Ambrose with a procession through the neighborhood with a mammoth donkey, Ethiopian umbrellas covering someone holding the Blessed Sacrament, procession of an Ethiopian icon of the Triumphal Entry, Ethiopian processional crosses and a New Orleans big band playing “Ride on King Jesus.” The Wednesday night Tenebrae service is an invitation into the darkness. The Good Friday Stations of the Cross integrates the singing of Negro Spirituals between the Stations. Throughout the rest of the liturgical year, Saint Ambrose has an Epiphany service of Lessons and Spirituals, an Ethiopian Evensong, and Blessed Martin Luther King, Jr. and Blessed Absalom Jones Sundays, and we have an active liturgical dance ministry.

[The Palm Sunday processional at Saint Ambrose includes Ethiopian umbrellas covering someone holding the Blessed Sacrament, procession of an Ethiopian icon of the Triumphal Entry and Ethiopian processional crosses. Photos courtesy of Saint Ambrose, Raleigh]

The congregation worships outside on several occasions. One is a Holy Eucharist at Pullen Park under an oak tree, acknowledging the fact that many African American churches began outside, worshiping under hush harbors and brush arbors. We worship annually on North Topsail Beach, the location of the former Episcopal Colored Retreat Camp, one of the few beaches where African Americans could own property during segregation. Other worship services throughout the year honor our church’s members, contributions and legacy.

One parishioner recently said, “The way Jesus is depicted at Saint Ambrose makes Jesus relatable to me as a black woman and deepens my personal relationship with God.”

Saint Ambrose strives to disrupt the legacy of racism and white supremacy present when churches gather to worship, and it is something every congregation can do. Unexamined and misunderstood church practices can do more to reinforce racism than disrupt it. We need disruptive preaching, teaching, hymns, images and liturgical practices. We are all God’s children, and in ensuring Christian practices reflect every one of us, the goal is to help lead all Christians into a deeper and more authentic experience of God through Jesus Christ.

The Rev. Jemonde Taylor is the rector of Saint Ambrose, Raleigh, and a member of a five-person group recently awarded a $400,000 grant from the Henry Luce Foundation to do a film and multimedia project on gentrification, race and theological education and practice.

Tags: North Carolina Disciple