Disciple: History and the Historiographer

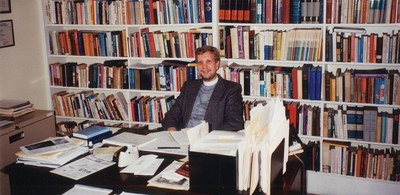

The Rev. Dr. Brooks Graebner brings history to life

By Christine McTaggart

Among the many traditions of the annual diocesan convention, perhaps none is so anticipated or so enriching as the Thursday night history presentation. Led by the Rev. Dr. Brooks Graebner, every session brings to life a slice of diocesan history, giving voice once more to those who played integral roles and weaving together events and lessons of the past with the realities and challenges of the present.

Graebner’s ready smile and gentle demeanor often cloak the deep faith, passion for history and fierce intellect that combine to ensure the history of the Church and diocese Graebner holds so dear is ready and waiting to be shared with current and future generations. Added to that is his skill in teasing out how history can provide perspective and guidance while navigating today’s tumultuous climate; one has to speak with him for only a few minutes to realize what a rare and gifted individual he is.

Graebner recently retired from St. Matthew’s, Hillsborough, where he served as rector for 27 years. Happily for anyone who has ever learned from him, he has not retired from his role as diocesan historiographer; there he remains, where he’ll continue to develop historical programs as well as research and write the second volume of The Episcopal Church in North Carolina, focusing on the years 1960-2015.

How did a love of history and a call to serve in The Episcopal Church converge to create the man we know today? As it happens, both were seeds deeply sown from his start, and the story of their growth is as interesting a tale as any Graebner loves to relate.

DEEP ROOTS

Graebner is the child of professional historians. His father was a historian of American diplomatic relations, while his mother’s focus was on Native American agricultural methods in Texas and Oklahoma.

“I grew up around the history profession, just around the dinner table,” said Graebner. “I’m sure my interest in it can be traced to that.” His parents encouraged not just his interest in history, they taught him to value it as well.

When Graebner entered the University of Virginia in 1970, it was no surprise he took history courses as part of his undergraduate study. One of his first courses was a study of African-American history; it was the university’s first-ever course on the topic. “A lot of my interest in African-American history can be traced back to that course,” said Graebner.

Some of his studies were guided by the influence of others. Graebner was drawn to professors he found “particularly inspiring and interesting and who encouraged me. Since I wanted to study with them, I learned to share their interest in their particular areas of study.” It was the influence of one such professor that led Graebner to a crucial crossroad in his life’s journey. The professor “directed my honors thesis,” remembered Graebner, “and since his field was American religious history, that’s what I studied.”

Some of his studies were guided by the influence of others. Graebner was drawn to professors he found “particularly inspiring and interesting and who encouraged me. Since I wanted to study with them, I learned to share their interest in their particular areas of study.” It was the influence of one such professor that led Graebner to a crucial crossroad in his life’s journey. The professor “directed my honors thesis,” remembered Graebner, “and since his field was American religious history, that’s what I studied.”

Even without the influence of a memorable and supportive professor, religious history was a natural path for Graebner to explore. He grew up in the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod, a denomination whose founding included involvement from Graebner’s great-great-grandfather. His great-grandfather was a seminary professor in the church, and his grandfather a pastor. “It sort of defined our family’s religious identity,” said Graebner. “So I was very interested in learning about and understanding that branch of Lutheranism more broadly. That was my initial interest in studying church history.”

Between the desire to explore his own roots and his professor’s influence, Graebner focused his undergraduate study with a major in religious studies with a concentration on American religious history.

CHANGE OF PLANS

About the time he was studying in Virginia, the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod underwent a rupture that stemmed from internal politics and discord on the direction the church would follow. The split was painful for his family, and it left Graebner with the realization he would not be following in any footsteps by becoming a minister in that church.

Instead, he moved to North Carolina and entered Duke Divinity School in 1973. He charted a course toward becoming an academician instead of a parish minister. He hadn’t considered a career as a member of the clergy in any other church, but providence gently stepped in to nudge him in that direction.

While in college, Graebner had been asked to serve as the organist in the small church his family attended. Though trained as a pianist, he wasn’t trained as an organist, so he “took a few lessons, and

then I subjected everyone to on-the-job-training for three years.”

When word got out in Durham he had experience as an organist,

Graebner made himself available to local churches when a substitute was needed. In the summer of 1979, it was St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Durham that called.

He spent a few weeks filling in and “didn’t think much more about it,” until a few months later when St. Luke’s rector (and future bishop of the Diocese of North Carolina), the Rev. Bob Johnson, called and asked if he would serve as both interim organist and choir director for a couple of months. As so often happens, those few months turned into a much longer stay. “I agreed to do it,” said Graebner. “And the rest, as they say, is history.”

Over the course of three years at St. Luke’s, Graebner continued to serve on-and-off as organist and choir director, while his wife, Chris, also became active in the church, eventually holding lay leadership positions around children’s ministry and education. By 1982, he began conversations with Johnson about entering the ordination process in The Episcopal Church.

“Chris and I looked at our lives and saw they were being transformed for the better,” remembered Graebner. “I felt at home in the Episcopal Church, and I grew to love the liturgy. I found myself thinking Bob lived a very fulfilling life, and his sermons were thoughtful, constructive, intellectual and practical.” His leaning toward academia began to share space with something more spiritual. “I started to think I might really like my primary vocation to be a parish priest,” he said. “I didn’t jettison my interest in history, but I really wanted the range of experiences and engagement with people that you get in parish ministry.”

He pursued the path while continuing his studies at Duke Divinity, and by the time he was ordained, he also held a doctorate in American religious history.

A PERFECT FIT

Graebner served as assistant to the rector at St. Peter’s, Charlotte, before answering a call in 1990 to become rector of St. Matthew’s. He settled in to life in Hillsborough, returning often to Durham to teach courses in Anglican and Episcopal history at Duke Divinity School. But it wasn’t until 2000 that he again became invested in his own historical research and writing. That year, he took a sabbatical and spent 10 weeks immersed in the history of St. Matthew’s along with the Episcopal Church in North Carolina. It was also the year he was invited to join the board of directors of the Episcopal Church’s historical society, putting him in direct contact with the people writing Episcopal Church history for seminaries.

Graebner served as assistant to the rector at St. Peter’s, Charlotte, before answering a call in 1990 to become rector of St. Matthew’s. He settled in to life in Hillsborough, returning often to Durham to teach courses in Anglican and Episcopal history at Duke Divinity School. But it wasn’t until 2000 that he again became invested in his own historical research and writing. That year, he took a sabbatical and spent 10 weeks immersed in the history of St. Matthew’s along with the Episcopal Church in North Carolina. It was also the year he was invited to join the board of directors of the Episcopal Church’s historical society, putting him in direct contact with the people writing Episcopal Church history for seminaries.

“From that year on,” he said, “my excitement and interest in the history of the Episcopal Church only continued to grow.”

In 2007, then-bishop the Rt. Rev. Michael Curry offered Graebner an appointment as diocesan historiographer. He happily accepted, and for the last decade, Graebner and Lynn Hoke, diocesan archivist, have preserved and integrated church history with contemporary life through programs like History Days and the Thursday night presentation at the annual convention.

“I am so grateful for the privilege of being the diocesan historiographer and to have had so many opportunities to share with the Church what I’ve learned,” said Graebner. “It is enormously rewarding and deeply satisfying, and I am sincerely grateful to be able to serve the Church this way.”

A KEY TO UNDERSTANDING

When asked why history is important, Graebner responded with a laugh. “Let me count the ways,” he said. “History is important because the present never exists in a vacuum. There is always a set of forces and decisions that brought us to any present moment, and understanding [that] process is enormously helpful for understanding where we go from here.”

Because, Graebner explained, history is not just about learning facts and dates. It’s about providing a framework for understanding the present. Beyond finding history intrinsically interesting, “I think for the life of the Church or society, the importance of historical study is to provide us – as fully as it possibly can – a reconstruction and understanding of how we got where we are now. Who are the people who shaped our identity? What is our inheritance? How can we be good stewards of that inheritance?” With some aspects of our history so clear and other parts somewhat obscure, Graebner believes “it’s helpful to look at it in its entirety and understand it as comprehensively and carefully as we can.”

History also provides context for the times in which we’re living now. As a church, we seek to bring reconciliation to social injustice, racial inequality and sociopolitical turmoil. We’re trying to do it in a time when everyone has a public voice, and they’re not afraid to use it. It makes the tasks all the more complex, and it can easily start to feel we’re in a world that is at an all-time low. But history tells us otherwise.

“There’s no such thing as a golden age in the history of the Church where everything was wonderful and perfect and uncontested,” said Graebner. “There’s never been a period when people lived smooth and uncomplicated lives. Even as we face difficult choices and challenges that for us are daunting, we’re not the first people to have difficult experiences. The Church has lived through crises, and that can give us confidence moving forward.”

Indeed, examining the past and understanding its context can shed light on our present and help to create strategies that will allow the Church to contribute to a positive impact on social change.

“The past does not give us a clear blueprint for the future,” said Graebner, “but it does provide signposts that can be very, very useful as we move forward.”

And it’s because of the Rev. Dr. Brooks Graebner that the Diocese of North Carolina has those signposts to follow.

Watch Graebner's presentation with the Rev. Jemone Taylor to the 202nd Annual Convention, “One great fellowship of love? Theological convictions and ecclesial realities in the racial history of the Diocese of North Carolina.”

Christine McTaggart is the communications director for the Diocese of North Carolina.