Disciple: Historic Foundations: Uncovering History

St. Michael’s, Raleigh, explores local history of race and real estate

By the Rev. Greg Jones

Anyone who has lived in downtown Raleigh, near North Carolina State University, or gone to the airport from Raleigh has spent a fair amount of time on Wade Avenue. It goes from downtown all the way out west, where it connects to Cary and merges into I-40. In the area close to St. Michael’s, Raleigh, there’s a little street off of Wade Avenue, just past Oberlin Road, called Baez Street. It cuts over to Grant Avenue. Why should these streets be of any interest to anyone who isn’t familiar with the City of Oaks? Well, it turns out these three road names of Wade, Grant and Baez bear the fingerprints of a very interesting and long-buried story involving race, real estate and Raleigh.

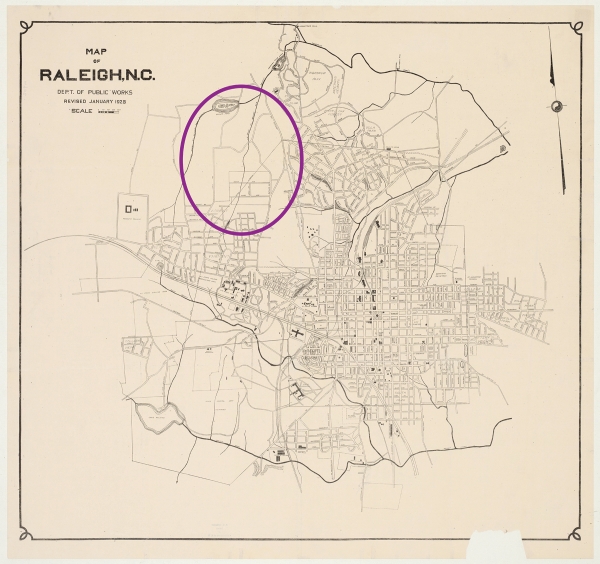

[Pictured: This section of an archival 1928 city master map of Raleigh includes the undeveloped Lewis farm area (circled) that would eventually house both the Oberlin community and St. Michael’s.]

THE DESIRE TO KNOW

I have always found historical research interesting, and a number of years ago I began a long research project into the history of St. Michael’s church property and the surrounding neighborhood. I was motivated by a couple of key interests. First, since my parish was founded only in 1950, and I am now its long-serving fourth rector, I wanted to capture as much as possible the memories of people who have been at St. Michael’s since its founding. Second, as a person with a deep interest in the history of Raleigh’s venerable Oberlin Community, a Black community begun after the Civil War, I always wondered if there were any connections between our property and the people of Oberlin, the boundaries of which are close by. Finally, I have a keen interest in simply knowing as much as can be known about the whole history of this place, going back as far as I could go.

My research began by talking to members of my parish who have been here since the start, along with neighbors who remember when this area was undeveloped woodlands and longtime Oberlin residents. I did a lot of walking, driving, hiking in creek beds, and looking for the old ruins of farm buildings. I consulted 19th- and early 20th-century maps and spent countless hours looking at Wake County land records. Thanks to digitized plot maps, ancient handwritten deeds and archived copies of Raleigh newspapers going back to the early 1800s, I was able to dig deep into history to identify the families that owned both the land upon which our church sits and the wider vicinity.

I looked at the prehistory of Wake County, learning about its geological formations. I then read about the pre-Colonial history of the area and the various Native American groups for whom this area was something of a crossroads. I learned that for thousands of years, the land we call Wake County has been home to human beings, as attested to by thousands of arrowheads and pottery shards found over the decades. Even today, new Native American artifacts are easily found. In the past few centuries, the region was something of a border area between several tribes, typically of the Iroquoian language group. Interestingly, the Neuse river takes its name from the Neusiok people, who were encountered in the late 16th century by English colonizers. Also quite active in the area were the Occaneechi and Tuscarora peoples.

After the conquest of this area by the English, it took some time for what is now Wake County to become of particular value to the colonizers, as early favor was with the rich lands in the eastern part of the state. It was in the late 18th century that Wake County began to establish its foothold, as the state capitol was placed on a single square mile on land formerly belonging to the Hunter family. Large populations of enslaved persons were brought into the area alongside the growing white population.

I did a survey on foot and searched books and records for the remaining colonial buildings in the area, of which there are few. But I found in the land records and newspaper accounts the families who owned the lands around St. Michael’s.

THE FIRST FARM

As it turns out, the street adjacent to St. Michael’s, Lewis Farm Road, tells much of the tale. I discovered this entire neighborhood, to the tune of more than 500 acres, was once a dairy farm, whose final owner—before it became a real estate development in the 1920s—was Dr. Richard Henry Lewis. Lewis was the longtime senior warden of Christ Church, Raleigh, and a close friend of the Rt. Rev. Joseph Blount Cheshire. He was a physician and Renaissance man like few others. His daughter, Nell Battle Lewis, became a prominent journalist and public figure in Raleigh well into the 1950s. The Lewis farm, called Cloverdale, included the rock quarry currently located underneath the Harris Teeter at Glenwood and Oberlin. The unique light-colored stone from that Lewis Farm quarry is something of a signature for Raleigh, visible in many old area buildings, including Christ Church’s parish hall and Broughton High School. The Lewis Farm included all of what would become the Budleigh neighborhood, from Oberlin Road to Beaverdam Park. It had at least two ponds: One would later be called Lake Boone, and the other, now drained, sits on the wooded ravine section of our church property. Indeed, a longtime neighbor of the church told me how the creek on our property used to be dammed up to create a pond.

Notably, in my research into the Oberlin community, I saw a short piece in The News & Observer from the 1890s telling how baptisms were once held in “Dr. Lewis’ pond” by members of the historically Black Wilson Temple United Methodist Church, located at Oberlin and Wade, just a short walk from the Lewis Farm. If those baptisms were indeed located on the site where St. Michael’s would be built, that would be the earliest known religious activity in this place.

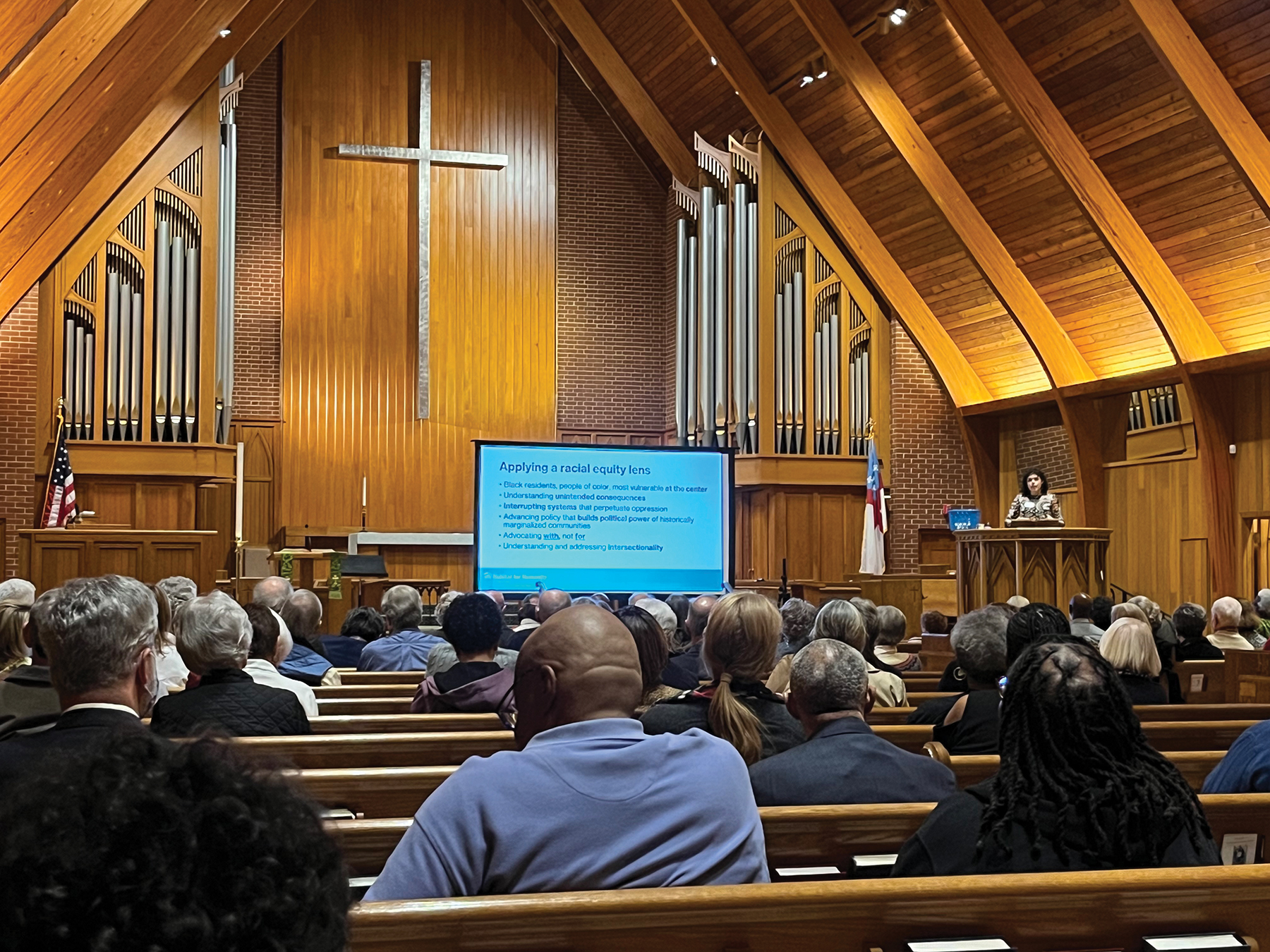

[Pictured: On January 31, St. Michael’s, Raleigh, hosted A Race & Housing Dialogue, which featured a viewing of the documentary “Segregated by Design” and a conversation with leaders from Habitat for Humanity, including Jacquie Alaya (pictured), and other area congregations. Photo by the Rev. Greg Jones]

WHAT’S IN A NAME

As I learned in my research, street names tell quite a lot of things. Fairview Road near our church, for instance, is named for the horse farm that abutted the Lewis farm and is now the Hayes Barton neighborhood. Its course through Budleigh is built upon Lewis’ dirt path that led to his milk cooling barns along the creek at what is now Lewis Circle. Manning Place is named for the Manning family that intermarried into the Lewis family and who were among the early owners of sections of the divided farm.

But what about the names of Wade Avenue, Grant Avenue or Baez Street? Those streets today enclose a section of Raleigh filled with new apartment buildings, low slung duplexes and just a few small older houses. They are only a few hundred yards away from the old Lewis farm boundary. And this is where I think the story gets interesting.

At the Civil War’s end and continuing rapidly during Reconstruction, nearly the entire length of Oberlin Road became a Black village outside the city of Raleigh. From what is now Hillsborough Street and the heart of NC State’s old campus to Oberlin Middle School near Glenwood Avenue, the length of Oberlin Road was populated almost entirely by Black families. There were only a few exceptions: the Fairview farm, the Lewis farm and a large tract of undeveloped land belonging to the descendants of the Cameron family that eventually became Cameron Village, now renamed the Village District. Nell Battle Lewis would observe in one of her weekly columns in The News & Observer that the Lewis farmhouse, where she spent an idyllic childhood before World War I, was the only home in the area where white people lived.

As has been well-covered in recent years by various local historians, in articles and at least one documentary, the Oberlin community included a school, a university, a dignified graveyard, churches and businesses and was home to several thousand Black professionals, tradespeople and merchants. A quick tour through the graveyard, still located just off Oberlin Road, reveals hundreds of grave markers, many of which tell of the education level, profession, military service and family connections of these prominent Black citizens of Raleigh.

A lesser known subset of the wider Oberlin story begins around 1870, when some of the farmland that formerly belonged to the Whitaker family (of Whitaker Mill Road fame) was parceled off just west of Oberlin Road. It was subdivided and plotted into a Black neighborhood and given the name of San Domingo. The names of its streets were Grant Avenue for President Ulysses S. Grant; Wade Avenue for abolitionist and Ohio Senator Benjamin Wade; Butler Street for General Benjamin Butler, a radical Reconstructionist; and Baez Street for Buenaventura Baez, president of the Dominican Republic.

It is amazing to consider that when you drive down Wade Avenue and see little Baez Street, you are seeing the toponymical evidence of a Black neighborhood built in Raleigh in the 1870s and named for three Yankees and the president of a Black island republic. It was done during the same time frame when President Grant was in discussion with President Baez about the United States annexing the island. Indeed, Grant conceived that the island might become a haven for newly liberated Black persons whom he knew would likely suffer in the postbellum South—which turned out to be very true.

But just as the United States did not annex the island republic, the San Domingo name soon faded from the Raleigh development, as the residents of the section preferred the proud name of Oberlin for their community. Indeed, in 1872 one letter from an Oberlin citizen to The News & Observer makes this very point. “Dear Sir,” the letter reads. “You will please do us the kindness to correct the many errors you have unknowingly made in the name of our flourishing little village. It is not... San Domingo... but Oberlin.” The editor of The News & Observer published the letter with a testy reply that the paper would call it what they wanted to call it.

While the wider Oberlin community would continue on well into the 20th century, and many of its original homes, buildings and even descendants still stand, much has been erased. The San Domingo subsection is perhaps the best example of this erasure. Within just a few decades, much of the land between Wade Avenue and Grant, and down from Butler just past Baez, became an affordable white neighborhood. Other parts were developed into the more upscale sections we now see.

Indeed, in a South that claims it doesn’t want to erase history, it has done just that. For instance, the name of Butler Street was changed to Chester. Perhaps somebody knew that Benjamin Butler had authored the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 and co-authored the Civil Rights Act of 1875—and they didn’t want monuments to Union generals to stand, even in the form of names on signs. In the same way, in the mid-1950s when Wade Avenue was greatly expanded, the history books began to claim it was named for some other guy named Wade. Wikipedia still says it was named for Stacy Wilson Wade, a North Carolina politician, who wasn’t even born when the first section of Wade Avenue was created and named for a Reconstruction Republican from New England.

Most historians of Oberlin say that the expansion of Wade Avenue was the death knell for the golden age of the Oberlin Community. Moreover, the farm lands that adjoined Oberlin (and the one-time San Domingo section) were all developed into highly restricted neighborhoods, with discrimination against Black citizens enshrined in the first covenant outlined in the deeds.

As part of our parish’s desire to understand history and our place in it, I shared my findings at St. Michael’s. Where our own local history touched on broader subjects, such as Jim Crow in general or the Wilmington massacre in particular, I offered some depth. The contemporary chapters of the story on race, real estate and Raleigh were discussed just last month, when St. Michael’s hosted, in conjunction with Habitat for Humanity and St. Matthew’s A.M.E., Raleigh, an evening of conversation and questions around race and housing. It has been and continues to be my hope that our parish will not erase history, but rather will continue to uncover history, using what we find as an impetus and inspiration for going forward justly.

The Rev. Greg Jones is the rector of St. Michael’s, Raleigh.

Tags: North Carolina Disciple / Racial Reckoning, Justice & Healing