Disciple: From Assistants to Leaders

Suffragan Bishops in North Carolina

By the Rev. Dr. Brooks Graebner

Deeply enshrined in the Christian tradition is the principle of having a single bishop in every community to safeguard the faith and order of the Church. St. Ignatius of Antioch, writing in the early second century, declared, “You must all follow the bishop as Jesus Christ [followed] the Father…let no one do anything apart from the bishop that has to do with the Church.” The Church in a given place could have multiple priests and deacons, but there would be only one bishop.

AND THEN THERE WERE TWO

But what happens when there’s enough work for two bishops in a given community? To address this challenge, the medieval church in England developed the practice of appointing suffragan or “supporting” bishops to help fulfill the duties of the diocesan bishop. In doing so, the principle of having a single bishop in charge of the diocese was upheld, but some of the work of the bishop was delegated to an assistant. The diocesan bishop principally functioned as an officer of the state, and the suffragan performed the sacramental acts.

At the Reformation, the Church of England continued to make provision for suffragans, but the practice fell into disuse as the spiritual and temporal duties of the episcopate were once again more fully integrated. When the American Episcopal Church was organized following the Revolution, the Constitution and Canons made no provision for suffragan or permanent assisting bishops. Instead, dioceses were authorized to elect assisting—now called coadjutor—bishops only if the diocesan bishop was having trouble fulfilling his duties by reason of “old age or permanent disability,” and if the assistant would one day become the diocesan.

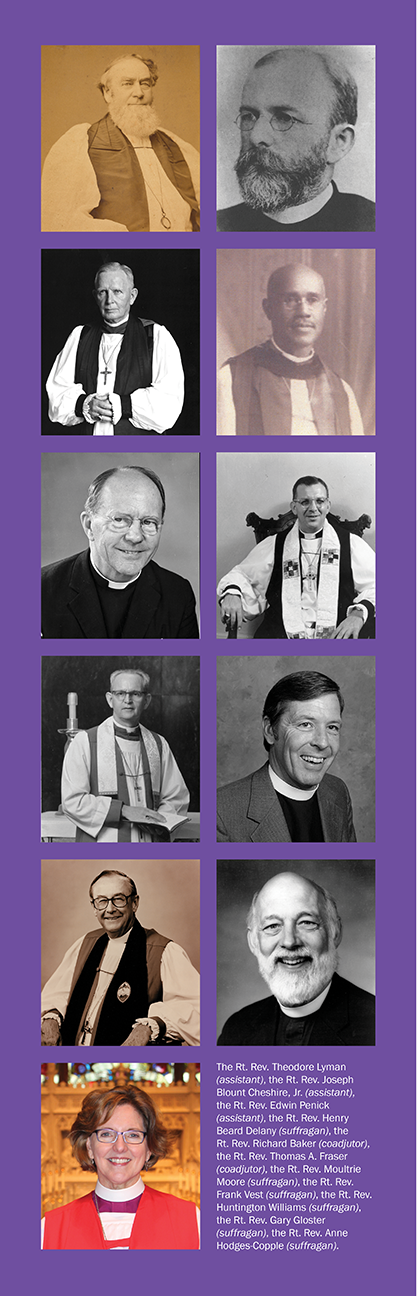

This is precisely what happened in North Carolina, when the Rt. Rev. Thomas Atkinson, by reason of his own declining health and the increasing demands of a growing church, called for the election of an assisting bishop. The Rev. Theodore Lyman was elected and served as Atkinson’s assistant from 1873 until Atkinson’s death in 1881; thereafter, Lyman became the bishop and served for another 12 years. He was, in turn, succeeded by the Rt. Rev. Joseph Blount Cheshire, Jr., who was elected assistant bishop just a few months before Lyman’s death. Cheshire served for 25 years before calling a successor. He and the Rt. Rev. Edwin Penick served together for 10 years until Cheshire’s death in 1932, when Penick assumed diocesan leadership.

Renewed interest in making provision for suffragan bishops started in the 1870s, both in England and America. The advantage was simply this: The diocesan bishop didn’t have to wait until incapacitation by age or declining health to call for episcopal assistance. Moreover, suffragan bishops made an attractive pool of candidates from which to elect diocesan bishops, since the Church could “judge by the manner in which they discharge their duties in that capacity, how far they are fitted for a wider sphere and weightier responsibility.” Still General Convention was reluctant to authorize suffragan bishops, concerned about creating what some detractors called a “sub-episcopate,” or two classes of bishop.

LEADERS IN THEIR OWN RIGHT

What finally swayed General Convention toward authorization of suffragan bishops was the desire on the part of some southern dioceses in the Jim Crow era to provide African-American bishops for work in black congregations. In North Carolina, under the leadership and hard work of Archdeacons the Rev. John Pollard and the Rev. Henry Beard Delany, more than 40 black congregations were established between the Civil War and World War I—enough to justify having a black bishop to minister to them. The constitutional change permitting suffragan bishops was passed in 1910; the Rt. Rev. Henry Beard Delany was made Suffragan Bishop of North Carolina in 1918 and served until his death in 1928.

Although Delany served with great diligence and effectiveness, persistent ambivalence about a racial episcopate on the part of both blacks and whites kept this practice from being continued. But the racial episcopate was never the underlying rationale for suffragan bishops, and The Episcopal Church began to utilize them in accordance with the arguments first put forward in the 1870s, namely, to afford dioceses additional episcopal assistance without necessarily having to choose a successor to the diocesan bishop.

In North Carolina, our Church had already undergone two diocesan divisions, one in 1883 and another in 1895, relieving some of the necessity for additional bishops. But as the Piedmont began to experience considerable economic and population growth after World War II, it was clear the diocese needed two full-time bishops. In 1951, the Rt. Rev. Richard Baker was elected coadjutor to serve under Penick until Penick’s death in 1959. As soon as Baker became the diocesan, he followed suit and called for a coadjutor. In 1960, the Rt. Rev. Thomas A. Fraser was elected, and they served together until Baker’s retirement in 1965.

At the 1966 convention, his first after becoming the diocesan, Fraser said he wouldn’t call for an assisting bishop right away. He changed his mind in less than a year. But instead of calling for a coadjutor, Fraser called on the diocese to elect a suffragan. Fraser was just 50 years old and expected to serve for another 15 to 20 years, making the naming of his successor premature. So, in 1967, the Rev. Moultrie Moore, then serving as rector of St. Martin’s, Charlotte, was elected the suffragan. He served alongside Fraser until 1975, when he was elected Bishop of Easton in Maryland.

The same thing happened when the Rt. Rev. Robert Estill became our diocesan bishop in 1983. He, too, called for the election of a suffragan at the beginning of his tenure, and the Rev. Frank Vest, rector of Christ Church, Charlotte, was chosen. Vest served in this diocese from 1985 to 1989, when he was called to be Bishop of Southern Virginia.

Estill then issued a call for a suffragan to succeed Vest, and the Rev. Huntington Williams, rector of St. Peter’s, Charlotte, was elected in 1990. But this time the pattern was reversed. Upon Estill’s retirement in 1994, Williams became the transitional bishop, providing pastoral and administrative continuity while Estill’s successor as diocesan, the Rt. Rev. Robert C. Johnson, assumed leadership. That pattern continued under Johnson: He called for a suffragan a year into his episcopate, and the Rev. Gary Gloster, vicar of the Chapel of Christ the King, Charlotte, was elected in 1996. Once again, the suffragan was asked to provide transitional leadership when the Rt. Rev. Michael Curry succeeded Johnson in 2000.

After Gloster’s retirement in 2007, Curry met the need for additional episcopal assistance through an appointment process, utilizing the gifts and graces of individuals who were already bishops: the Rt. Rev.

William Gregg and the Rt. Rev. Alfred “Chip” Marble.

But by 2013, Curry was ready to follow in the footsteps of Fraser, Estill and Johnson and call for the election of a suffragan to share in episcopal oversight and to implement the Galilee Initiative. The Rt. Rev. Anne E. Hodges-Copple was elected to fulfill this mandate. The rest is history: In 2015, Curry was elected to serve as Presiding Bishop, and for the third time our suffragan was called to transitional leadership—this time as Bishop Diocesan Pro Tempore. As she now resumes her role as full-time suffragan, her leadership will offer invaluable service to our new diocesan, the Rt. Rev. Sam Rodman.

LEADING THE WAY

Initially a position of assistance, the office of bishop suffragan has evolved into one of leadership. Bishop Hodges-Copple has proven this repeatedly and in many ways in the last four years, and it is with great excitement that we follow her forward in answering the call to ministry.

The Rev. Dr. Brooks Graebner is the historiographer for the Diocese of North Carolina and rector of St. Matthew’s, Hillsborough.