Disciple: An Intergenerational Tapestry

How St. John’s, Wake Forest, is bringing generations together through worship

By Summerlee Walter

When Louis Mullinger first heard the Rev. Sarah Phelps’ idea for a new experimental worship service at St. John’s, Wake Forest, his reaction was immediate and firm.

“I thought it was the worst idea I’d ever heard.”

From Mill Hill in London, England, Mullinger is a life-long Anglican who appreciates the regularity, familiarity, and via media ethos of The Episcopal Church. He also has children and grandchildren who accompany him on Sunday morning, and so, knowing that the new service was designed to meet the needs of families and children, he decided he’d better check it out “to reinforce [his] prejudices.” The thing about Mullinger, though, is that he’s able to change his mind. And he did. Immediately.

“I was completely wrong, and right from the start, I thought this was fantastic. If I had to choose one service to go to, I would probably choose Tapestry now.”

[Image: The Rev. Mawethu Ncaca explains what is happening during the Eucharist to young worshipers at the St. John’s, Wake Forest, intergenerational Tapestry service, which takes place each Sunday at 11:15 a.m. Photo throughout by Veronica LaFemina]

Whatever you’re imagining when you hear “experimental worship,” Tapestry probably isn’t it. This isn’t slideshows, stage lights and a drum kit. Nor is it a kid’s worship service with kid music. The service follows the outline of Holy Eucharist as prescribed in The Book of Common Prayer, but the elements are reimagined for a modern intergenerational audience with “an attention span that’s closer to 45 minutes than 60 or 75” who “are inspired by artistic expression of all kinds.” The service is inclusive and casual, usually held outdoors in the columbarium unless inclement weather moves everyone into the education building. Jeans, shorts and even pajamas are welcome because worshipers move around during Tapestry. At the front of the seating area is a makers’ table, where everyone is invited to engage artistically or grab a fidget to help them concentrate throughout the service.

The service follows the familiar pattern of music, lessons, sermon, prayers, offertory, peace, communion and dismissal—the Liturgy of the Word and the Liturgy of the Table. The why behind each element of the service is the same as it has been since ancient times. It’s the who and the how that change each week. Participants in the service are not preassigned, so anyone who turns up might be asked to serve as an acolyte, reader or chalice bearer. With special permission from Bishop Sam Rodman, children are involved in all aspects of the liturgy, including as chalice bearers.

“We love how interactive [Tapestry] is, and it’s a bit more relaxed for my 7-year-old son who is wiggly during traditional mass,” said parishioner Karen McIntyre. “Caelyn [12] loves how much she can participate in mass, and our church is one of her favorite places on the planet. My mom even prefers it to traditional mass. It provided a fellowship and community we were looking for in a church.”

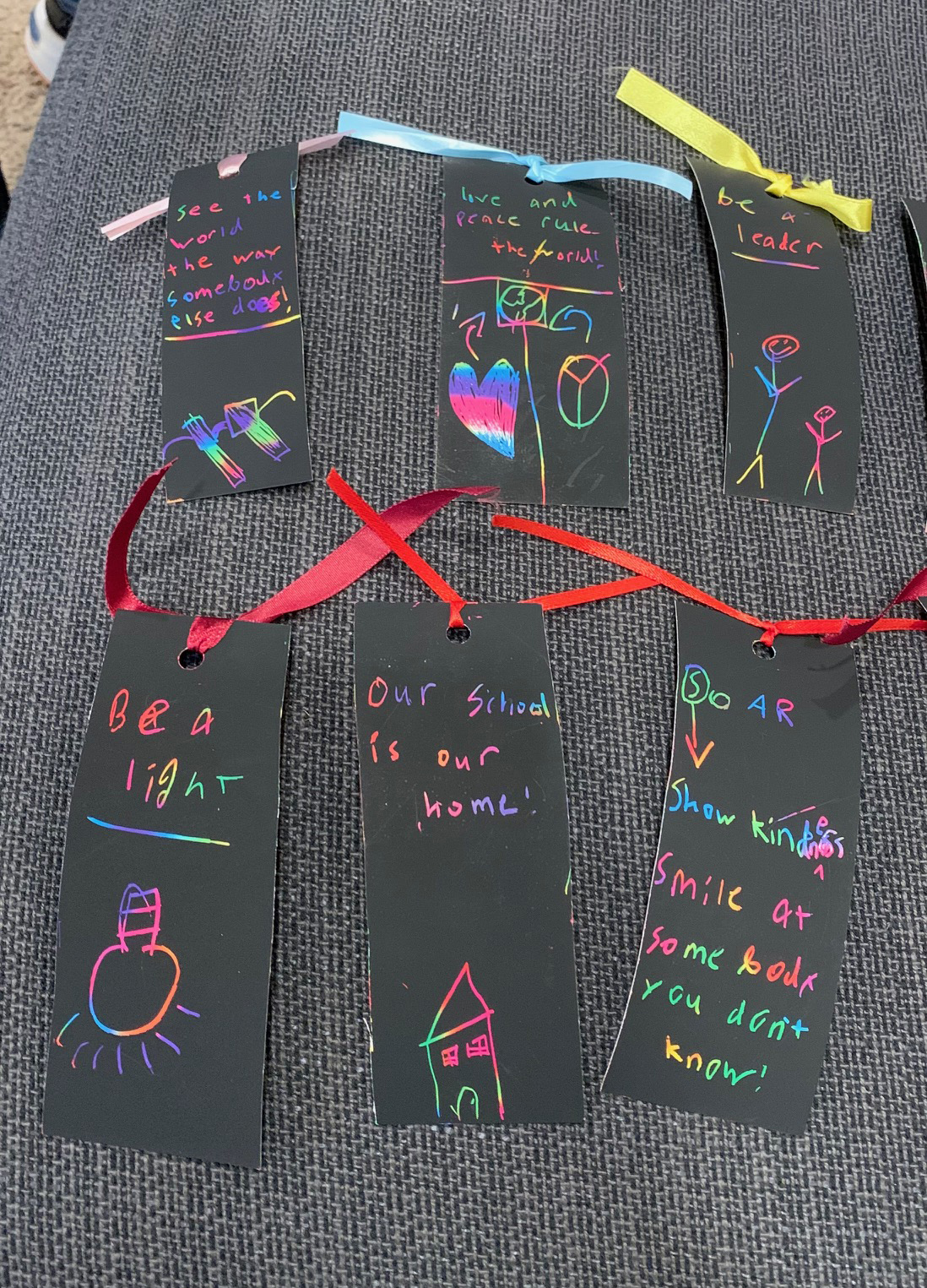

Veronica LaFemina and her family have found a similar home in Tapestry. Her children, in kindergarten and third grade, want to be involved, but there is no role for them in a traditional Sunday morning service. At Tapestry, however, her 6-year-old daughter regularly serves as crucifer and has distributed communion several times. Her eight-year-old son is quieter, but he’s always listening, and he has found his ministry at the maker table. During the past several months, he has created and distributed more than 75 inspirational bookmarks to fellow parishioners.

"It’s a safe space for him to be creative and show how he wants to make the world a better place, and he is celebrated and not judged,” LaFemina said.

WHAT FAMILIES NEED

The idea for Tapestry arose out of dual concerns about space and appealing to young families. St. John’s sanctuary seats 250, if people pack into the pews, something that has become less appealing post-pandemic. The church was on the verge of running out of space for its 9:30 a.m. service in both the sanctuary and the parking lot. At the same time, fewer families—and especially those with young children—returned to church after COVID-19.

“All the church growth literature says if you have a ‘successful’ service at one time, replicate it,” Phelps said. “Do what works. But [the 9:30 a.m. service] works for older people and already formed Episcopalians.” She noted that many parents of young children themselves had not attended much Christian formation beyond fifth or sixth grade, and some felt ambivalent about returning to church after being away during their college and early career years. Even in a truly welcoming congregation like St. John’s, parents often feel self-conscious in a formal church setting when their children make noise or need to move around.

“So what parents are doing is bringing the kids in, then shushing them until they get taken away for Sunday school,” Phelps explained. “Then they come back, and the parents are shushing them some more. So what’s the draw, really?”

[Image: A sampling of the bookmarks made by Veronica LaFemina’s eight-year-old son as an offering to the community.]

As the rector of St. John’s, Phelps began dreaming about intergenerational worship that kept children with their parents throughout the entire service instead of sending them away for 20 minutes of formation during the readings and sermon. She learned from reading about intergenerational worship and talking to clergy colleagues and parents about what was and was not working about traditional church. From that reading, thinking and conversing, Tapestry arose.

“I came to the conclusion that intergenerational ministry and intergenerational relationships were going to be the thing that helped younger families connect and want to be part of the church more than any particular program, and especially anything that required families to walk in the door, then age segregate, which is what our traditions have been,” Phelps said.

A FAMILIAR SERVICE FOR A NEW AGE

The next step for Phelps was to ask for special permission from the bishop to experiment with worship at St. John’s. Since Tapestry does not use Episcopal Church-approved liturgical resources, Bishop Sam Rodman granted permission to try Tapestry for local use (i.e. only at St. John’s) for one year, with further discernment to follow after that time. With permission secured, Phelps started experimenting.

The Tapestry service is intentionally shorter, more sensory and less spoken word- and print-based. Instead of placing pressure on parents to schedule their children as participants in the service well in advance, acolytes and vergers are assigned on the spot, and Phelps prints small service cards to help them remember what to do. The chalice bearers, too, get assistance from having the words they are supposed to say taped to the chalice. The priest explains what is happening and what the sacrament means right before distribution. Similar short conversations pepper the liturgy. The movements of the liturgy—carrying the cross, lighting the candles, bowing—are all present, but the execution is not as formal and tidy as in a traditional worship service.

The music is more accessible to singers of all levels than the traditional Episcopal choral repertoire. The call and response music is a type of paperless singing from Music that Makes Community, an organization that “practices communal song-sharing that inspires deep spiritual connection, brave shared leadership, and sparks the possibility of transformation in our world.” It’s kid-friendly but not kid music. The congregation will sing the same songs for six to eight weeks before they cycle out, so everyone really learns the music.

For the readings, Phelps uses the narrative lectionary from Luther Seminary, which is arranged chronologically to help people understand the big arcs of Scripture; a liturgical planning resource called Spill the Beans from the United Kingdom; and the Revised Common Lectionary, depending on the liturgical season. The readings take the form of biblical storytelling, “which is what the readings are supposed to be about anyway,” as Mullinger puts it. Sometimes the storytelling looks like Godly Play or a skit. The sermon is replaced by small conversation groups of at least three generations, during which the youngest worshipers are invited to share their ideas and questions first.

The Prayers of the People also invite interaction and creativity, taking different forms each week. Sometimes the prayers involve lots of silent reflection. Other weeks, worshipers might rotate among prayer stations with pictures that represent the major categories of prayer outlined in The Book of Common Prayer. Phelps draws from resources like Enriching Our Worship and sources from New Zealand and Australia, where the intergenerational worship movement is more developed than it is in the United States.

If pulling together Tapestry every week sounds like a lot of work, it is. As a result, sustainability is a real question with which Phelps struggles. The learning curve is intense, and every week is very much an experiment from which the church continues to learn as it finds its way with this nascent ministry.

“There’s a part of me that’s like, ‘You are crazy’ because it’s really hard,” Phelps said. Tapestry began in the midst of several staff transitions, so Phelps has largely crafted the liturgy herself each week. Now that there is a certain amount of buy-in amongst the congregation, she is working to pull together a team to help plan the service.

[Image: An example of biblical storytelling from the Tapestry service.]

THROUGHOUT ALL GENERATIONS

Since Tapestry started on the first Sunday in October, the service has averaged between 40 and 60 attendees from the St. John’s congregation. Those who love Tapestry love it because it is so intentionally intergenerational.

“It was very important that [Tapestry] wasn’t just a children’s service.” LaFemina said. “My kids have tons of bonus grandparents, and I have tons of bonus aunts and uncles.”

It’s not just the young families that have found a home at Tapestry. “Some of the older people have said, ‘Oh yeah, this is my new service,’” Phelps explained.

Of course, not every family has decided Tapestry is the best fit for them. St. John’s also has made modifications to the traditional worship service to make it more welcoming and inclusive for families and children. Instead of Godly Play, which removed children from the service, the church instituted Pew Buddies, adult volunteers who look out for families with young kids and set them up with intentional worship bags full of worship aids—not the coloring sheets of old. Children ring the bell at the beginning of the service, bring up the offertory and say the dismissal at the end of the service. The church also is considering setting up a prayer ground play space near the altar so children can sit up front with their parents near them.

Regardless of their preferred service, families at St. John’s experience a church that welcomes the gifts of each of its members, across all generations. Even if that means a little mess or chaos, Phelps is okay with it.

“We try to speak to their spirit first, then work in the tradition.”

Summerlee Walter is the communications coordinator for the Episcopal Diocese of North Carlina.

Tags: North Carolina Disciple