Disciple: The Value of Telling Our Stories

How personal stories enrich our history

By the Rev. Canon Kathy Walker

Telling stories is a time-honored tradition. Most of us are quite familiar with Jesus and his parables in the New Testament. Parables were stories told by Jesus in understandable ways, using imagery familiar to the community in which he was situated. It was a profound way to impart important lessons still relevant today. Jesus used the parable of the Good Samaritan to demonstrate clearly the importance of expressing empathy towards others. He talked about humility through the parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector. Many can recount the moral of the parable of the rich man and Lazarus. Parables are specifically designed to move from your head to your heart for the greatest and most permanent impact. While we tend to remember those in the New Testament, it is important to note that parables were also told in the Old Testament. It is a form of storytelling that has a particular way of helping people more fully embrace disseminated information. The personal familiarity with the context of its setting and images facilitates comprehension.

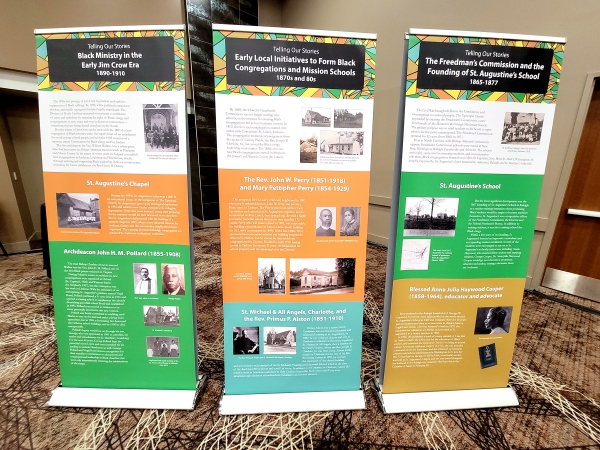

[Image: Three of the “Telling Our Stories” banners highlight the history of Black Episcopalians in the diocese. Photo by Christine McTaggart]

For the past 15 months, members of diocesan staff have embarked on a journey of recording videos to capture the stories of historically Black congregations in the Diocese of North Carolina from the perspective of the people in the pews. In the past, historical data has been gathered for all of these congregations. We know when the churches were founded, how they came into being and, perhaps, some other vital statistics about them. Through parochial reports, there is information on their levels of giving and the number of congregants. But there is more to every community than cold statistics. It is equally relevant to understand the history of these churches through the lives of the people there. It is a remarkable thing to sit at the feet of people typically in their 70s and 80s (though ages do vary) and hear their tales of what brought them to, and kept them attending, those churches.

AN UNEXPECTED GIFT

In 2021, the dean and president of Virginia Theological Seminary, the Very Rev. Ian Markham, traveled to Durham to host a reception for seminary alumni. It was slated as a fundraiser for the school. I engaged Markham in a conversation about a project on which I really wanted to embark in this diocese. I told the dean I needed funds from the seminary instead of the other way around. We chuckled a bit, and then he asked me seriously about the context of the project I imagined. I told him about the idea for “Telling Our Stories” and that we would need about $10,000 to complete a video project and a set of traveling banners depicting the current roster of Black churches. After a short while, Markham looked at me and said, “The money is yours.”

I was shocked. I pitched the idea halfheartedly, not really expecting to get the full funding from that one institution. I am filled with gratitude to Markham and Virginia Theological Seminary for their wonderful gift to the diocese. Years from now, historians and lay people in the Diocese of North Carolina will be able to watch the stories of historically Black congregations told by Black people: their hopes and dreams, their limitations and their resilience.

There are currently 11 historically Black congregations located in urban centers and rural areas from Charlotte to Tarboro. All Saints’, Warrenton, is a special mission currently in the midst of redevelopment plans for a robust future that continues to celebrate the nearly two centuries of accomplishments of Black people in and around Warren County.

At one time there were more than 60 Black congregations in the Diocese of North Carolina. Some were relocated to our sister dioceses of East Carolina and Western North Carolina. The bulk of them, however, remained in this diocese and closed over time for any number of reasons. It is probably safe to say there was pain associated with the closing of all of those churches, as there is pain in the closing of any of our beloved communities where people have gathered over a long period of time.

Black churches, in particular, have long been communities where people felt safe to tell their stories. Traditionally, people felt safe to gather with their children or organize around social justice issues. Community organizing has long tentacles in historically Black churches, and many activists regularly met Black folks in their churches to offer assistance and guidance and to inspire action. Pastors, too, used storytelling and the word of God to galvanize people into action. Storytelling is just as important today, for many of the same reasons that were relevant 50 or 100 years ago.

COUNTLESS CONTRIBUTIONS

Every church represented in the “Telling Our Stories” video was asked to identify one or two leaders who would speak on behalf of the congregation. They were encouraged to talk about their remembrances of entering the church at whatever age they were at the time. Some realized they had been in those church communities since they were children. Others came to the church as young adults, while still others joined a particular congregation later in life as they moved into a new neighborhood. However they became engaged in their worshiping community, the one thing that was clear was that the church had a profound impact on their lives and a deep influence on how they saw the outside world.

Each of them had a story to tell about ministries in which they took part, whether it was singing in the choir or outreach or administration. One told a story of evangelism at Chapel of Christ the King, Charlotte, where a parishioner was tasked with using the van to pick up children on Sunday mornings and bring them to church to participate in services and learn about the word of God. After church, they would be treated to lunch and desserts. Those same children were encouraged to return to the church during the week for additional activities. Why was it important? It kept children and young people safe, and it gave them a place where they could be nourished spiritually, mentally and physically. The church became an after-school space during the week for homework assistance, peer group meetings and a safe place to play.

In other churches, leaders talked about preparing meals and collecting food products for neighborhood distribution, understanding that as they had done unto “the least of these,” they had also done for God. The Jesus parables inspired those parishioners to create community within the communities in which they lived. They felt strongly that God had called them to serve. Service continues to this day.

Everyone was expected to do their part to keep churches alive and flourishing. There are descriptions of schools created for Black children during the Jim Crow era. The stories make clear that parishioners and their leaders were willing to make tremendous sacrifices to educate children and pursue a life of greater equality. They embraced the principles found in the baptismal covenant and trusted that God would see them through. Some members recounted feelings of neglect by diocesan leaders as requests were made for support. In spite of that, they are mainly stories of joy and resilience. There is a sense of pride in keeping church communities together during very difficult and challenging times. Some expressed concerns about the aging populations currently in their pews as they continue to dream of their churches flourishing once more.

This information is now well documented. Nearly two dozen people were interviewed for the “Telling Our Stories” project with a couple more still on the horizon. In keeping with the diocesan mission priority of Racial Reckoning, Justice and Healing, listening to stories that involve the tribulations and jubilations of the Black community in this branch of The Episcopal Church is very notable. It is important to understand the past as the future beloved community is being created. Hopefully, these stories will serve both as joyful remembrances and as an acknowledgement of a past that deserves to be brought to light.

The Rev. Canon Kathy Walker is the canon missioner for Black ministries for the Diocese of North Carolina and the host of the “Roundtables on Race” podcast.

Tags: North Carolina Disciple / Racial Reckoning, Justice & Healing