Disciple: Seeing Jesus Through an Indigenous Lens

Jesus’ teachings and Indigenous world views have much in common

By the Rev. Bradley Hauff

Over the last few years, the wider world has begun to understand the abuses and injury done to Indigenous children forced to attend boarding schools, many of them faith-based, in the 19th and 20th centuries in the name of assimilation. The Episcopal Church has begun its own reckoning with its role in these schools, including the funding of independent research into the church’s archives, a call for a comprehensive proposal addressing the legacy of the schools, and an exploration of “options for developing culturally appropriate liturgical materials and plans for educating Episcopalians across the church about this history.”

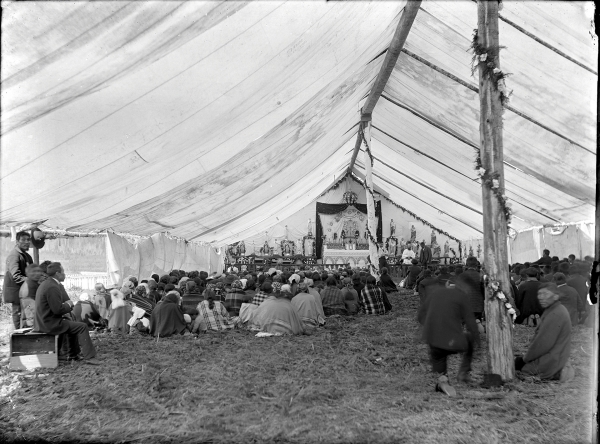

[Image: First Nations people at worship in Sechelt, British Columbia, Canada, circa 1890. Courtesy of the Vancouver Public Library.]

Given the revelations related to the schools, as well as the multitude of ways Indigenous people have been harmed over centuries, including by the church, it might be natural to assume that given the choice, Indigenous people would want nothing to do with Christianity. Yet that is not necessarily the case.

Indigenous people have had a relationship with Christianity that dates to the beginning of colonialism. It continues to this day, and while some Indigenous people have renounced Christianity, many have a church affiliation. Given the devastating impact that churches have had on Indigenous people, questions often asked include, why would an Indigenous person want to be Christian? Is it possible to be authentically Christian and Indigenous? Can Jesus be seen and recognized apart from the narratives and strategies of colonization? Indigenous scholars and theologians have considered these questions, and their conclusions have been conflicted.

The fact remains, however, that many Indigenous people are both authentically Indigenous and authentically Christian. How is this possible? The answer lies in seeing Jesus through an Indigenous lens.

THE DOCTRINE OF DISCOVERY

Indigenous people in what are now known as the Americas, and throughout the world, continue to be impacted by the effects of European colonization. Virtually all people are aware of this, even those who have been exposed to narratives of history that minimize or even deny the harm that was done: land theft, slavery, enforced acculturation and genocide. The recent popularity of the movie “Killers of the Flower Moon” is an example of this awareness. There is currently a focus on the Doctrine of Discovery, as well, and how this philosophy inspired and directed the processes of colonialism. Through the lens of the Doctrine of Discovery, the vast influence of the Christian church is revealed, with troubling implications, both for Christians and Indigenous people.

The Doctrine of Discovery shaped the approach of European nations and the Christian church to Africa and the Western Hemisphere, yet few people in the United States have heard of it. Even fewer can explain what it is. It is hardly ever taught in history courses, particularly in public schools, and it hasn’t been written about widely until recently. There are two plausible reasons for this.

First, unlike the Constitution or the Declaration of Independence, there is no single document known as “The Doctrine of Discovery.” The doctrine is comprised of the philosophies expressed in three papal decrees: “Dum Diversas” (Pope Nicholas V, 1452), “Romanus Pontifex” (Pope Nicholas V, 1455), and “Inter Caetera” (Pope Alexander VI, 1493). In “Dum Diversas” and “Romanus Pontifex,” the pope gave the monarchs of Portugal and Spain the spiritual authority to capture and control any territories and subjugate any people discovered in Africa, as long as the people and lands were not already under the authority of a Christian nation. These decrees undoubtedly influenced the Spanish monarch in commissioning the voyage of Columbus. In “Inter Caetera,” issued after the Columbus “discovery,” the pope extended this authority to the Western Hemisphere and its Indigenous peoples.

The Doctrine of Discovery is, therefore, an unholy union between church and state, granting to European nations the divine right to take land and subjugate people, and laying the foundations for African slavery and the genocide of Indigenous people. The Doctrine of Discovery spread to England in 1496, when King Henry VII granted to John Cabot and his men the authority to investigate, claim and possess any lands and riches discovered in the New World for the English crown, provided they were not previously claimed by another Christian nation.

I believe these stunning revelations are the second reason that the doctrine hasn’t been widely taught. It exposes European nations—and the Christian church—as greedy entities motivated by power and wealth rather than the Gospel and human freedom. It looks bad, and it is, in ways that many have difficulty even grasping.

Americans can neither separate themselves from nor blame Europe and the pope for this. America empowered this colonization process. In the late 1700s, Thomas Jefferson, who referred to Indigenous people in the Declaration of Independence as “merciless Indian savages” who were to be exempt from the basic rights granted by God to humankind, was influenced by the Doctrine of Discovery and found it to be central to the new narrative of America. In 1823, Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall ruled in Johnson v. McIntosh that Indigenous people have no right to their land. In his ruling, he cited King Henry VII’s patent to John Cabot as a justification. And while Marshall effectively reversed his decision nearly 10 years later in Worcester v. Georgia, his ruling was ignored by President Andrew Jackson, and the Trail of Tears followed. In the late 19th century, the influence of the Doctrine of Discovery became evident in its American interpretation that came to be known as Manifest Destiny: the God-given right of Europeans to seize control of America from its original Indigenous inhabitants. Additionally, the figure of Columbia (a feminine name associated with Columbus) became recognized as the mythological personification of America and was depicted in numerous works of art at the time, such as John Gast’s “American Progress” and the iconic Statue of Liberty.

The traditional narrative of America is one that is rooted in the Columbus discovery and Manifest Destiny mythologies. It traces back to the Doctrine of Discovery, which had its origins in the Christian church. It is a narrative of European dominance, Christian dominance and white supremacy. At its core, it is a narrative that extols the Doctrine of Discovery and its devastating effects on the Indigenous people of the Western Hemisphere, millions of Indigenous people from hundreds of tribes who had been living in organized societies for at least 30,000 years. It is a narrative teaching that Indigenous people were heathens and that God was somehow an absentee landlord of the Western Hemisphere until 1492. It justified slavery, land theft and genocide. It continues today as the unacknowledged foundation for systemic racism. It is why many in the United States who are white supremacists also consider themselves to be Christians and don’t see any conflict in it. The Gospel of Christ was brought to the Western Hemisphere along with this narrative, and the two narratives have yet to be successfully separated.

So why, you might ask, would any Indigenous person today have a relationship of any kind with Christianity?

[Image: First Nations people at worship in Sechelt, British Columbia, Canada, circa 1890. Courtesy of the Vancouver Public Library.]

RECOGNIZING CHRIST

In the 19th century, there were three main reasons that Indigenous people became church affiliated. It had to do with survival, a need to openly express our spirituality and the recognition of the Christ as a universal figure in our beliefs.

First, Indigenous people were in danger and needed the help and advocacy of churches, which provided them with life-saving assistance of various kinds and intercessory communication with the federal government. The Indigenous boarding schools, operated by churches and the government, arose from this context, and while the schools at the time were seen by dominant American society as beneficial and philanthropic to Indigenous children, they would later be revealed as cruel instruments of enforced assimilation and cultural genocide. Nevertheless, an Indigenous person in the 19th century without a church affiliation was in a very precarious situation.

The second reason has to do with the nature of Indigenous people: our worldview, our spirituality and our traditional ways. We are a spiritual people. We believe in the Great Spirit, the sacredness of all things in the Cosmos and the inextricable connection of all that exists. This is demonstrated by a Lakota phrase that proclaims all things as related, human and non-human: mitakuye oyasin (translated, “all my relatives”). It is so central to our life that it is inconceivable to be any other way. Tragically, in the 19th century, most forms of traditional Indigenous ceremonies were made illegal. Consequently, Indigenous people did not have the right of freedom of religion, a right not officially acknowledged until 1981, 57 years after Indigenous people were made U.S. citizens. Because we are inherently spiritual, we had to have some type of outward expression of our faith. Christian churches were the only practical option.

The last reason so many Indigenous people became church affiliated may surprise you: Christ was already known by Indigenous people prior to the missionary work of European churches. They didn’t know about Jesus of Nazareth, the first century Palestinian Jew, but they knew Christ, whose teachings and wisdom were present in our spiritual narratives. My Lakota ancestors, when they heard the Christian Gospel stories for the first time, instantly understood them, to the extent that they thought Jesus must be a Lakota. Because only a true Lakota would be so brave, so generous, so compassionate, so wise. In this sense, the missionaries brought to Indigenous people a faith we already had.

Indigenous people today, while continuing to live with the lasting, intergenerational effects of genocide, are in a bit of a different situation than our ancestors. We don’t need the church to survive, and we can now outwardly express our traditional spiritual beliefs and rituals. The third reason, however, remains valid, and I believe it is the only way to a genuine congruence of Indigenous spirituality and Christianity.

Indigenous author and philosopher Vine Deloria, Jr., a one-time seminary student and the son of an Episcopal priest, believed it was impossible to be authentically Indigenous and Christian. He renounced Christianity and embraced his identity as an Indigenous person, one separate from the church and Christ. In contrast, Steven Charleston, an Indigenous (Choctaw) Episcopal bishop, maintains that it is possible, if Jesus is seen from an Indigenous perspective as a Native messiah, one who fulfills Indigenous spiritual expressions and who exemplified Indigenous values and morals in his teachings and way of life.

Jesus taught many things that are consistent with an Indigenous understanding of life. He encouraged us to learn from non-human teachers, such as the birds and the trees, about how to live more faithfully. He interacted with nature frequently, as with the non-productive fig tree (Matthew 21:18-19, Mark 11:12-14), assuming the role of a native elder scolding a relative for not living up to standards, something commonly seen within Indigenous communities. He interacted with nature in the wilderness where he was tempted, living through an experience that is basically identical to the Indigenous vision quest.

The transcendence of Christ and culture is something that has precedence in the Bible. In the Acts of the Apostles, during the first Jerusalem Council, the issue was brought forth as to whether or not Gentile converts to Christ had to become Jewish first. The answer was “no,” a Gentile could convert directly from his or her previous religious understanding.

Somewhere along the line, that rule was lost, and Christianity and culture (namely European culture) became solidly united and enforced in the spiritual and cultural indoctrination of Indigenous people under the authority of the church and empire. It was a mistake with horrific results.

Looking at Jesus through an Indigenous lens can have great value to all Christians. It is an example of the universal, eternal presence of Christ within all peoples, transcending all human differences. It helps us to look closely at our faith and identify what is Gospel based and what is culturally based. It shows us there are different ways of knowing the presence of Christ beyond what we have experienced. It is long overdue for us to become acquainted with the Native Messiah Jesus.

Abandoning the Columbus discovery narrative is central to this. It allows for the honest acknowledgement of Indigenous people in this country and what happened with, and to, us. It allows for truth-telling. It promotes an honest examination of our past. It dispels the myth and atrocity of white dominance. It tells Indigenous people that we are not relics of the past, that we are very much still here, and that we are a significant part of both the American and Christian stories.

The church can and should be a central part of making this transition happen. By doing so, the church will help correct the mistakes of the past that it created in the first place, while liberating the Gospel from narratives based in greed and hate.

The Rev. Bradley Hauff is the Indigenous missioner for the Episcopal Church and a member the Oglala Sioux Tribe (Lakota) of Pine Ridge, South Dakota.

Tags: North Carolina Disciple / Racial Reckoning, Justice & Healing